The constant growth and complexity of the building code has been a concern of ours for years. Simply put, the beastly size of the code is the bane of most architect’s existence, and while we love a good hyperbolic rant, we’ll be focusing on the no-nonsense, objective data here. A recent talk we gave for the Northwest Eco Building Guild allowed us the welcomed opportunity to perform a deep-dive into the actual metrics of the International Building Code (IBC), which proved extremely insightful. This article presents our findings related to the frequency of building code releases, and how the document has changed over the years—and we admit that there may be a tirade here and there just to keep our wits in check.

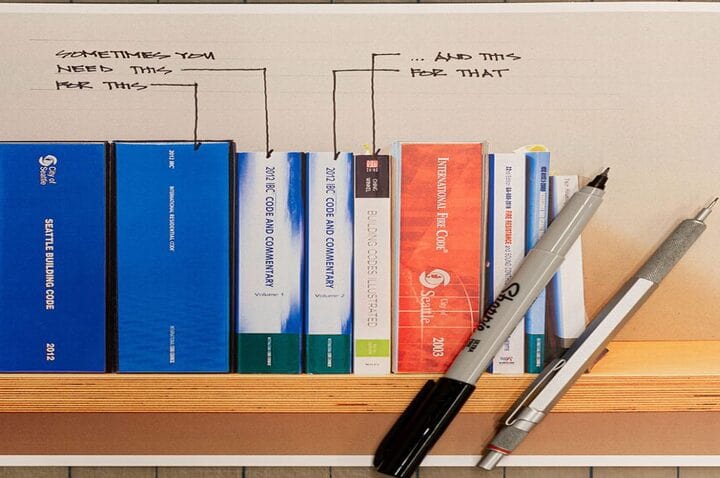

The photo shown above captures what might be the most significant evolutionary moment of the code over the last 100 years. Up until the mid-1990s, the code was a small book that you could throw in a bag on your way to the jobsite. This datapoint alone represents volumes about how architects used to work. Up until the 1990s, architects could reference the code on the jobsite and problem solve in the field. With its current size and weight, it now requires its own table in most offices. Because it can’t simply be transported in a bag, referencing the code and problem solving on the jobsite is much more difficult (hauling the current codes to the jobsite practically requires a trailer). So, the overwhelming size and complexity of these codes is partially responsible for turning architects into permit technicians rather than professionals who can roll up their sleeves and problem solve in the field. This photo begs the question of how this came to be.

This photo shows the relevant codes that were used here in the BUILD office up through 2016; note that the subsequent 2015 and 2018 codes have grown in size and complexity. These codes include: the International Building Code (IBC); the International Residential Code (IRC); the Seattle Building Code (SBC); Building Codes Illustrated, for when you need a drawing or diagram for the commentaries (we wish we were making this stuff up); a Fire Resistance manual for assemblies; two versions of the Accessibility Code, which sometime conflict with one another; and commentaries on the codes (because they’re written in such arcane language, it takes a separate book to translate them).

The International Code Council (ICC) releases a new UBC/IBC every three years, and jurisdictions have the option to adopt these codes as they like (the code was called the Uniform Building Code until 2000, or UBC, and then the title changed to the International Building Code, or IBC, from that point forward). Here in Seattle, an every three-year cycle of adopting a new code started in the 1940s, and has since become an industry unto itself. Companies have been formed for the sole purpose to steward the cyclical publication of the code, and an army of employees depend on each new release to make a living. So, it’s safe to say that this three-year pace isn’t going to ease up—if anything it will only become more frequent. The concern is, of course, do we really need new building codes every three years?

Additionally, with the IBC changing and being reissued every three years, there’s a subsequent trickle-down effect with each of these supplementary documents. Changes to the UBC or IBC have a direct impact on State and City amendments and all of the ancillary codes mentioned above.

The lack of housing in our cities is a national emergency. Here in Washington State, King County declared a homeless state of emergency in 2015, and the building code and permitting processes aren’t making things any better. It’s time for the industry to look back and realize that the trajectory of ever-increasing codes is going to harm the built-environment in the long term. It’s time to set a precedent of trimming and curating the building code every several cycles. It’s time to be smarter.

We want to underscore that the ever-growing building code isn’t just an inconvenience or a frustration, it’s a significant barrier standing in the way of a more equitable built environment and more just society. In our opinion, if we can’t re-evaluate and course-correct now, we’ll spend the next several decades playing catch-up, we’ll continue wasting valuable resources, and we’ll exacerbate social inequality. It’s really important to remind ourselves that everything discussed here is a mechanism contrived by humans. The size of the building code, the frequency with which it is adopted, and the content itself are all devices entirely made up by people. This isn’t to say that they don’t serve a purpose, but we’re simply proposing that we change what isn’t working.